Historic Tredegar Iron Works

- Tim Murphy

- Dec 21, 2018

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 24, 2021

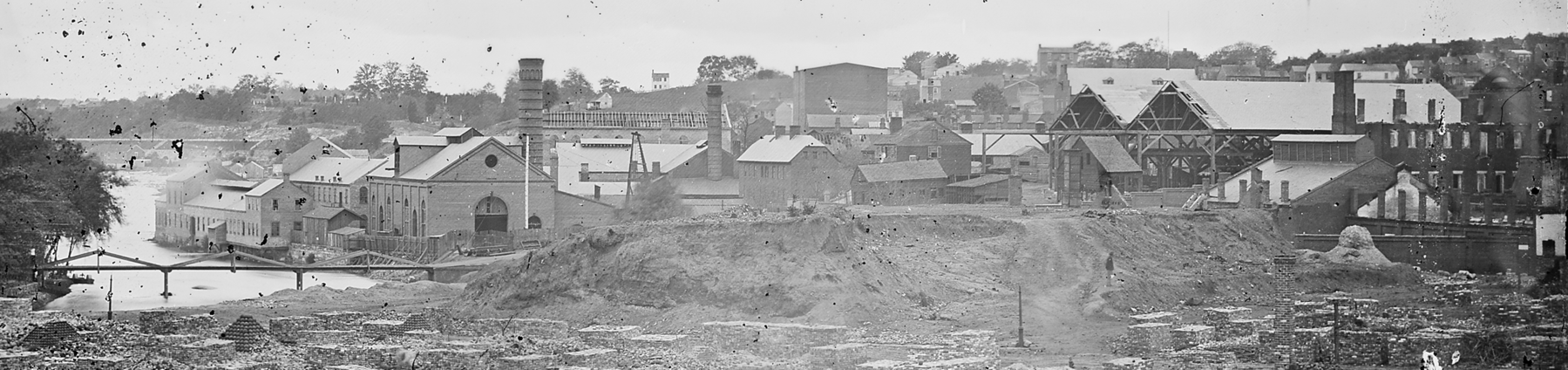

Richmond, Virginia, was the political and industrial capitol of the Confederacy—at its center was the Tredegar Iron Works. This massive industrial complex was once the fourth-largest iron works in the nation and the leading producer of armaments and munitions for the Confederate States. Tredegar barely survived the tribulations of the Civil War and proved to be a critical asset during Reconstruction. As the demand for iron declined in the 20th century, Tredegar’s prominence slowly waned and the facility was eventually closed. Today, its historic buildings have been restored by the National Park Service and its doors reopened to the public, providing an interpretive experience of Richmond’s Civil War History.

In May 1837, Francis Deane Jr. and members of the Virginia Foundry Company opened a small forge and rolling mill along the Kanawha Canal. The site was named ‘Tredegar’ in honor of engineer Rhys Davies and his men who emigrated from Tredegar Mills, Wales, to construct the facilities. Tredegar’s position along the James River offered much promise. Its close proximity to the canals and railroads provided unrestricted access to raw materials from Virginia’s interior and bountiful channels for the distribution of finished goods.

However, Tredegar’s formative years were far from lucrative. In the same month of the company’s founding, the United States experienced a devastating economic crisis: the Panic of 1837. The Panic was caused by President Andrew Jackson’s Specie Circular, the failure of the National Banks, and diminished agricultural production. The resulting depression lasted seven years and caused Tredegar numerous financial hardships. The turmoil continued in 1838 when Davies was stabbed to death by a fellow worker on site. The tragedy dealt a significant blow to the company’s leadership. Davies’ body was buried on Belle Isle.

In 1841, Tredegar hired Joseph Reid Anderson—a West Point graduate and assistant state engineer of Virginia—as a purchasing agent for the company. Anderson was an ambitious visionary who secured multiple government accounts for armaments and oversaw the greatest period of expansion in Tredegar’s history. Anderson’s contracts turned a considerable profit, which enabled Tredegar to evolve from a small iron foundry to a massive industrial complex that included a sawmill, locomotive works, and firebrick factory. The company also procured coal mines and blast furnaces across the state. In five short years, Anderson managed to buy out the company’s shareholders and become sole owner of Tredegar.

Anderson hired a diverse group of workers to operate the foundry complex. Immigrants from Germany and Ireland found gainful employment at Tredegar, as did many freed and enslaved blacks. Slaves, in particular, were taught valuable ironworking skill sets and placed in positions equal to white workers. Freed blacks even earned the same wages as whites, a practice seldom seen in Antebellum America. The relative equality displayed on Anderson’s part was not well-received by white workers. In 1847, a group of employees organized a strike in protest of the skilled work positions occupied by African Americans. Anderson did not take kindly to the demonstration and dismissed all those who partook in the strike from duty. He hired new workers and placed African American in even more high-level positions. In addition, Anderson provided housing, food, clothing, and medical care for his workers and enticed productivity with bonuses for exceeding daily quotas or by working overtime. By 1860, Tredegar (then called JR Anderson & Company) employed a workforce of 2,500 and was the primary iron-manufacturing center of the South.

Anderson was a staunch secessionist and exclusively sold his products to southern states following South Carolina’s break from the Union. In early 1861, a Gun Foundry was constructed in the Tredegar complex to meet the needs of the emerging Confederate Army and Navy. In fact, it was a Tredegar cannon that fired the opening shot at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

In May 1861, the Confederate capitol moved from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia. Confederate leaders made this decision based on Richmond’s industrial might—augmented by Tredegar’s iron production—and political milieu. Richmond was also home to the Confederate naval and marine forces. Rocketts Landings, a once-bustling shipyard located downstream from Tredegar, became a major wartime naval center and shipbuilding facility. The CSS Virginia was assembled there; its armor plates manufactured at the Tredegar Iron Works.

Tredegar struggled to maintain a viable workforce during the early stages of the war, as many of its employees either enlisted in the Confederate ranks or abandoned Richmond following secession. Between 1861 and 1864, the percentage of white workers at Tredegar plummeted from 86% to 25%. Joseph Reid Anderson, himself, served in the Confederate Army as a brigadier general (he returned to Tredegar after being wounded at the Battle of Frazier’s Farm in the summer of 1862). The foundry, and virtually all the industries of the South, increasingly relied on freed and enslaved black labor to sustain operations and meet the demands of the Confederacy.

One of the most active buildings at Tredegar was the Crenshaw Woolen Mill—a six-story structure that manufactured blankets and tents for the Confederate Army. The mill caught fire in the early morning hours of May 16, 1863. The flames spread throughout the industrial complex, damaging and destroying a majority of Tredegar’s buildings. The iron foundry was one of the few structures that escaped total destruction, which allowed Tredegar to maintain large scale armament production. By the war's end, Tredegar casted over 1,100 cannons and supplied nearly half of the artillery used by the Confederate Army.

On April 3, 1865, Richmond burned. With the Union Army closing in on the Confederate capitol, President Jefferson Davis ordered a mandatory evacuation of the city. Confederate defenders set fires around Richmond’s Warehouse District in an effort to prevent the industrial commodities from falling into Union hands. However, the flames became rampant and spread through much of downtown Richmond, reaching the periphery of the Capitol Building before being contained. The destruction was catastrophic and is known today as the Evacuation Burning. Miraculously, Tredegar survived the blaze thanks to Anderson’s Tredegar Brigade—a group of 350 workers who guarded the building from looting and demolition.

With the main industrial complex preserved, Tredegar was able to resume peacetime operations within months of Union occupation. Anderson was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in late 1865 and continued to operate the foundry until his death in 1892. In 1867, the Pattern Building was constructed in place of the Crenshaw Wool Mill—currently the site of Richmond’s NPS Battlefield Center—and by the early 1870s, Tredegar had doubled its prewar manufacturing capacity.

Tredegar’s postwar success was soon hindered by the Financial Panic of 1873. Essentially, the Panic resulted from the failure of Jay Cooke & Company, a brokerage house that provided railroads and other big businesses investment capital for expansion. When Cooke declared bankruptcy, banks that operated on his credit collapsed. A majority of Tredegar’s customers were northern railroads that were tied up in these failed banks. Without capital, they defaulted, leaving Tredegar with their debts. The company went into receivership in 1876 and managed to avoid liquidation. However, Tredegar lacked the capital to transition from iron to steel production, an impediment that would yield severe ramifications for future business endeavors.

Tredegar experienced steady business after the Panic and its resulting depression were resolved in 1879. The foundry assumed the role of a major arms manufacturer during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, providing artillery and naval shells for US forces during the Spanish-American War, both World Wars, and the Korean War. However, as iron fell out of favor for steel, so did Tredegar’s business. After 120 years of operation, Tredegar closed its riverfront location and sold the property to the Albemarle Paper Manufacturing Company (later the Ethyl Corporation) in 1957. All business operations at the location ceased by 1986.

The ironworks were purchased by the Richmond History Center in 1992. The organization restored much of Tredegar’s outdoor machinery and brick structures and established a small history museum in the Pattern Building. The enterprise was short-lived as it closed in 1995. The National Park Service acquired the property in 2000 and opened the present-day Visitor Center in 2003.

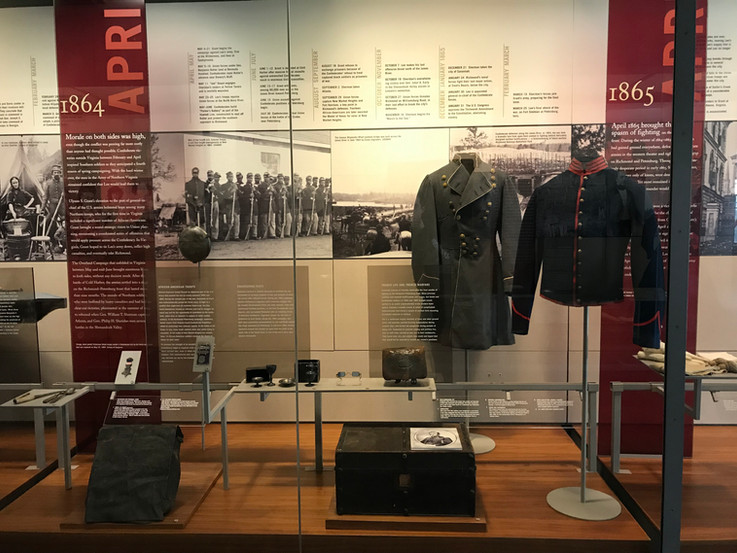

The refurbished Pattern Building stands today as a three-story testament to Richmond’s and Tredegar’s Civil War history. The upper-most story contains a self-guided museum filled with battlefield and home-front artifacts, auditory and written narratives from Civil War soldiers and citizens, and a short movie on the history of Tredegar. On the main floor, visitors can view scaled models of the Tredegar complex and observe how the site developed over the years. The second floor contains a map and documents room; however, this exhibit has been closed indefinitely due to flooding.

Across the way from the Pattern Building is the old Gun Foundry, which currently houses the American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar. This privately-funded museum provides visitors with a comprehensive examination of the Civil War, its causes, and its effects from the perspectives of Union, Confederate, and African American observers. Since this museum is separate from the National Park, there is a $12 fee for entry.

My visit to the Tredegar Iron Works was nothing short of phenomenal. There was a tremendous sense of historic significance the moment I stepped onto the site, like I was traveling back in time to the foundry’s heyday. The buildings are beautifully restored to their original grandeur and there is no shortage of information to be learned. The admission for the ACWC Museum is totally worth it, so I highly encourage you to check out both locations when you visit Historic Tredegar!

Visit the National Park website for more information on the Tredegar Visitor Center!

Check out the Library of Virginia's collection of business records from Tredegar!

Read The Tredegar Iron Works: 1865-1876 to learn more about the foundry's postwar production!

Read Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Virginia: A Study of Industrial Survival, 1873-1892 to learn more about the Panic of 1873's impact on the business!

Read The Tredegar Logistical Support in the American Civil War to learn more about the foundry's role in the Confederacy!

For some primary documents on Tredegar, visit the Civil War Richmond website!

For more information on the 1863 Crenshaw Mill fire, read this article!